This is the second in a very occasional series of posts explaining my academic research for non-academic audiences. Check out the first post for the rationale behind the series, and if anything seems wrong or doesn't make sense, let me know and I'll try to answer the best I can.

The study:

Tweeting conventions: Political journalists' use of Twitter to cover the 2012 presidential campaign, by Regina G. Lawrence, Logan Molyneux, Mark Coddington, and Avery Holton.

Journalism Studies. (It's paywalled, but I'll send you a PDF copy if you email at markcoddington at gmail dot com.)

What were you trying to find out?

The idea for this study came from

Regina Lawrence, a professor at the University of Texas (where I'm a Ph.D. student) who's been studying how political journalists do their job for a couple of decades. As frantic and spastic as political journalism (and especially campaign journalism) may seem at times, it's actually one of the most stable and settled forms of journalism we have in the U.S. The idiosyncrasies of political journalism were first nailed down in a definitive way in the early 1970s, and have been the subject of countless exposés and jeremiads since then — most famously, in journalism, in Timothy Crouse's classic on the 1972 campaign, "

The Boys on the Bus," and in academia, in Thomas Patterson's early 1990s critique of the campaign process, "

Out of Order." And frankly, they haven't changed much since then.

You're probably familiar with how campaign journalism works and why it doesn't work very well. Heck, you've probably ranted about it a few (or a few hundred) times yourself. But just to spell out exactly what we're all talking (and ranting) about, here are a few of the very well-defined traits that have made American campaign journalism so easy to loathe for the past few decades:

- Objectivity: It's ostensibly built around the idea that journalists can and should separate their opinions and values from the facts on which they're reporting. But objectivity often turns out to just mean a "he said, she said" style of reporting that refuses to do the work to evaluate competing claims and instead leaves them to us to scratch our heads over. It's meant to undergird a certain rigor in reporting, but on the campaign trail, it often means journalists pass on campaigns' claims without basic fact-checking.

- Lack of transparency: Objectivity does leave some wiggle room: Reporters often work within it to write more interpretively about how campaigns are trying to woo and manipulate voters (more on this in the next point). But the candidates' attempts to manipulate and negotiate with reporters themselves have historically been off-limits (though this is changing a bit). What's still an unmentioned issue among most reporters is their own influence in how campaigns are run — part of what Jay Rosen calls "the production of innocence." Journalists are a key part of setting the rules of political game, but we don't hear much — certainly not from them — about their own role.

- Horse-race journalism: Journalists' preference for reporting on strategy and gamesmanship rather than issues and substance is one of best-documented aspects of their campaign coverage. This style allows them to write incisively about the campaign while avoid charges of partisanship, but despite this show of independence, it can end up deeply influencing the trajectory of the campaign. It also leaves voters ill-informed about the voting decision they're making.

- Insider journalism: Partly because of the grueling and insular environment of campaign reporting that Crouse documented, it's been especially prone to insider-ism — a relatively bounded group of journalists talking to itself and to an even more tightly bounded set of sources from within and around the campaigns, and using this very narrow range of perspectives to gauge the conventional wisdom about the campaign. The result is a form of journalism and opinion that seems very removed from the concerns and viewpoints of people outside this bubble, and can be very easily debunked.

So that's campaign journalism as we've known it. But this is a pretty old model of political journalism, one that's rooted in what

Dan Hallin called the "high modernism" of American journalism — an era in the late 20th century when traditional journalism was powerful, prosperous, stable, and pretty much got to dominate the public sphere. But all of that has changed: Professional journalism's stability and authority have been rocked by a variety of forces — economic, social, political, and technological. The one we wanted to look most closely at was the environment for politics on Twitter, which could potentially challenge each one of these conventions of campaign journalism:

- Objectivity: Giving your opinions on things seems to be a core function of Twitter — if you're not sharing any of your opinions, you look like you don't know how to use it, or at the very least, everyone thinks you're pretty boring. So the norms of Twitter would seem to work against the careful, studied objectivity of traditional journalism.

- Lack of transparency: Here we run into another of Twitter's key uses (for better or worse): Sharing the mundane details of your day-to-day life. To the extent that those details involve reporters' work, that's an opportunity for a level of transparency we haven't seen before.

- Horse-race journalism: Here, the difference on Twitter might be more indirect. The public has repeatedly said in surveys that it prefers substantive issues to strategy coverage, so if social media users resemble the public in that respect and if they voice those preferences to journalists and if those journalists are listening and responding, then we might see some reduction in horse-race journalism there.

- Insider journalism: It's easy to see how this might change on Twitter, which opens the door for so many people outside the traditional media/political arena to have a voice, gain a following, and earn the attention of a small sliver of the American public. If that sliver includes political journalists, it could go a long way toward helping them open their reporting beyond the usual insiders.

In light of this potential, our overarching question was a pretty simple one: Do these classic attributes of campaign journalism still hold in the Twitter environment, or does something about them change?

So what'd you do?

We used a custom-built program based on Twitter's API to gather political journalists' tweets during the 2012 presidential campaign, then systematically analyzed a sample of them manually for a variety of characteristics that could indicate these journalistic practices.

We started by gathering a sample of 430 political journalists and commentators to collect tweets from. We identified a range of news organizations on a variety of platforms — 19 national news organizations, both traditional (New York Times, CBS, CNN, NPR) and nontraditional (BuzzFeed, Slate, Politico), and 76 other local news organizations in battleground states based on campaign spending amounts. We used a

database of media professionals to find any staffers with politics or campaigns listed as part of their job description or coverage area, then found their professional Twitter accounts.

We collected all of their tweets between the start of the conventions in August 2012 through Election Day, but for this study we only used the period during both parties' conventions. We wanted a focused, bounded sample from a point when nearly all political media attention would be trained on the same political events, which would help minimize irrelevant tweets and extraneous variance in the journalists' situations, allow us to more efficiently and directly compare groups within the sample. We collected about 39,000 tweets during the conventions, and once we sampled a random subset of those tweets we ended up with 1,629 tweets to analyze, with the non-political ones being excluded from the main analysis.

We then did some quantitative

content analysis, using five different people to go through each tweet manually and code it for several characteristics that we thought could help measure some of the dimensions we described earlier: Statements of opinions or personal identity and fact-checking for objectivity; talk about the journalists' work for transparency; discussion of candidate strategy, characteristics, and voting blocs (as opposed to issues) for horse-race journalism; and linking to and retweeting insider and outsider sources and seeking information from users for insider journalism.

One other note: I was the third author out of four on this paper, which in this case means I led the content analysis and chipped in on revisions of the review of literature and discussion of results.

What'd you find out?

The TL;DR version:

Journalists showed some willingness to deviate a bit from their traditional norms regarding objectivity, transparency, and horse-race journalism. But despite Twitter's potential to dramatically broaden the political conversation, they're still as resolutely insular as ever.

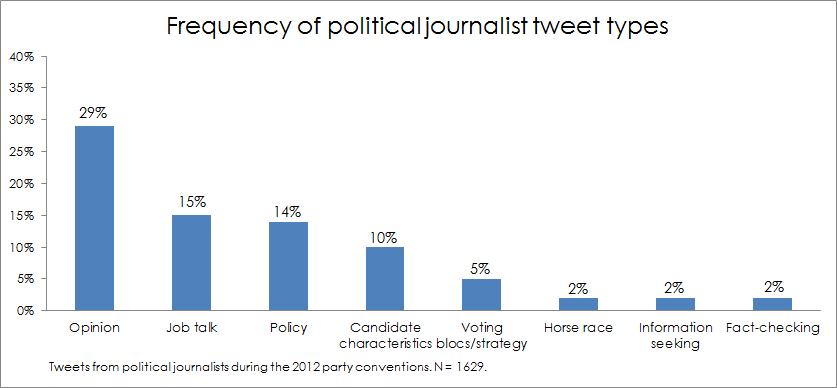

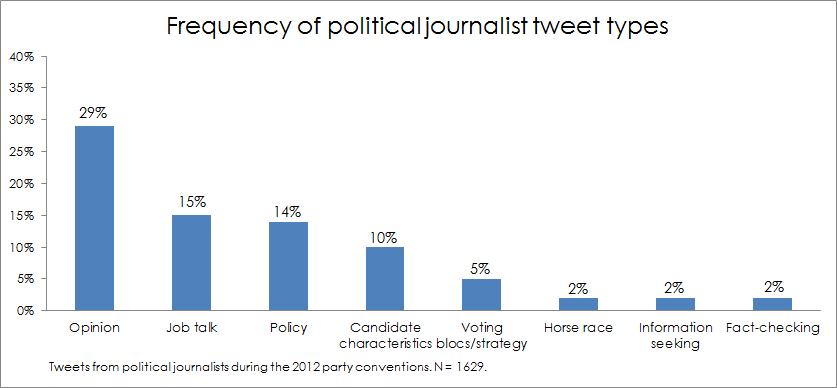

We'll start with this chart, which should give you a basic overview of the tweeting patterns we found (click to enlarge):

- Objectivity: Of the tweets we analyzed, 29% contained a statement of opinion, which we defined as using evaluative language or offering unattributed commentary beyond the facts of an issue. That's a pretty high number, especially since we pitched the tweets that weren't about the journalists' professional lives (i.e., work or politics). A sizable minority of our sample was made up of commentators rather than reporters, yet when we just included reporters, opinion was still at 24%. Interestingly, national reporters were significantly more likely to include opinions than local reporters, and not surprisingly, those in cable news were significantly more opinionated than those in broadcast news.

- Transparency: The amount of talk about journalism was higher than we expected, too: 15% of the tweets contained some sort of information or comment about journalists doing their daily work. Those tweets tended not to include information about the rest of the campaign, whether horse-race or policy. Now, these daily-detail tweets probably fall more reliably into the category of "tedious navel-gazing" than any meaningful form of transparency. But they're more than what we were getting before, which was pretty much zero.

- Horse-race journalism: This was, in our minds at least, the strangest finding. Only 2% of the tweets had a horse-race element, and only 5% mentioned a voting bloc. A bit more — 10% — mentioned a candidate characteristics (these were often paired with statements of opinion). But even more tweets than any of these (14%) mentioned a policy issue. This trend — more policy, less strategy — is the exact reverse of what's been found over and over again in campaign journalism. So maybe there's a bit more space for policy news and discussion on Twitter in the midst of campaigns than we thought. On the other hand, there may be methodological issues here: We had to define horse-race (whether a tweet mentioned a candidate's position in polls or fundraising) and campaign strategy (mentioning a voting bloc) pretty narrowly in order to achieve reliability between coders. So there may be more horse-race talk that our study wasn't able to pick up.

- Insider journalism: The results here weren't surprising, but they were still dismal. Of the links in journalists' tweets, 90% were to professional news outlets (46% to the journalist's own work), with only 10% going anywhere else. Of the journalists' retweets, 82% were other journalists, while 7% were what we defined as political insiders (candidates, campaign staff, consultants, interest groups), and just 11% were from anyone outside those two groups. Journalists also requested information from their followers in just 2% of all tweets.

Based on this study, political journalists on Twitter are loosening the traditional bounds of objectivity and horse-race journalism and even, to an extent, showing some transparency. And that's a meaningful development, something for which journalists deserve some commendation. But their conversation is a performative one, rather than something that's truly interactional. They're talking with fellow journalists, with the rest of us simply watching their conversation; to the extent that we try to enter it, our efforts are generally futile. In other words, campaign journalism is still made almost exclusively by a set of boys on the proverbial bus, except the rest of us are now pressing our faces to the windows, straining to hear and be heard. We can pick up the loudest bits and pieces of their conversation, and they, it seems, can barely hear us at all.